Polycystic liver disease (PLD) is a progressive disease, but only a small subset of patients develop severe symptoms. Supportive management is recommended for patients with mild symptoms, while patients with severe symptoms can be managed surgically, with liver transplantation being the only curative option. This activity reports on the diagnosis and management of PLD and explains the interprofessional team’s role in the management of patients with this condition.

Objectives: Polycystic liver disease treatment

- Describe the pathophysiology of polycystic liver disease.

- Review the risk factors associated with polycystic liver disease.

- Identify the indications for liver transplantation in patients with polycystic liver disease.

- Summarize elements of a well-coordinated interprofessional team approach to providing effective care to patients affected by polycystic liver disease.

Table of Contents

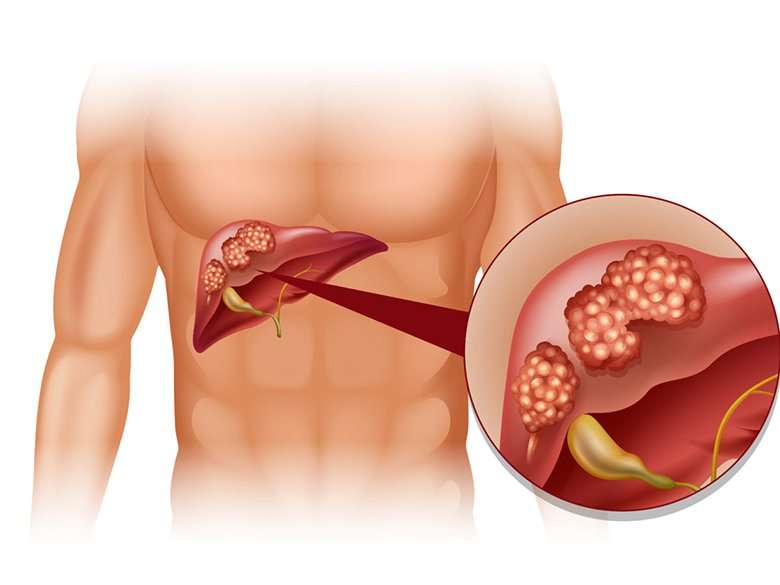

Introduction: Polycystic liver disease treatment

Polycystic liver disease (PLD) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by mutations in genes encoding for proteins involved in the transport of fluid and the growth of epithelial cells in the liver.[1] These mutations lead to the replacement of normal liver tissue with fluid-filled liver cysts. There are two distinct forms of PLD: PLD in isolation and PLD in association with polycystic kidney disease (PKD). The majority of patients with PLD are asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally on imaging.[2] However, in a small percentage of patients, hepatomegaly can lead to abdominal pain, distension, and compression of adjacent organs, potentially affecting the quality of life.[3][1] PLD is diagnosable using ultrasonography, a computed tomography (CT) scan, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). For the patient with symptomatic PLD, the main goal is to decrease liver volume. There are currently several surgical options available, including cyst fenestration, hepatic resection, and liver transplants. There are also medical therapies now under investigation.[4] Polycystic liver disease treatment This activity discusses the diagnosis and management of PLD.

Etiology

The cause of PLD is the result of mutations in several genes. In isolated PLD, germline mutations occur in the PRKCSH, and the SEC63 genes are in charge of making the proteins Sec-63 and hepatocytes and are responsible for fluid transportation and epithelial cell growth.[4][3] They are expressed on hepatocytes and cholangiocytes, although the underlying mechanism of how they are involved in cyst formation remains unclear. The second group of PLDs is those associated with PKD. There are two forms of PKD: autosomal dominant PKD (ADPKD) and autosomal recessive PKD (ARPKD). In this form of PLD, the kidney has the greatest involvement. Patients tend to develop renal complications such as renal failure, with most requiring dialysis and kidney transplants. The two genes believed to be the culprits for cyst formation in ADPKD are PKD1 and PKD2.[1] These genes are responsible for making polycystin 1 and polycystin 2, regulating fluid secretion and epithelial cell growth. The mutation of these genes leads to dysregulation of fluid secretion and abnormal growth, ultimately leading to cyst formation.[2] Most patients with ARPKD, on the other hand, die shortly after birth due to pulmonary complications.Polycystic liver disease treatment Those that do survive tend to develop liver fibrosis rather than cysts.[5]

Epidemiology

For a long time, it was thought that PKD patients were the only ones who could develop PLD. In the 1950s, isolated PLD was recognized as a distinct medical illness. In 2003, eight Finnish family analyses led to the genetic confirmation of this diagnosis.[6] In the general population, the prevalence of isolated PLD is 1 to 10 instances per 1000000 people, but the frequency of ADPKD is 1 in 400 to 1 in 1000 cases. Approximately 80–90% of all PLD patients have ADPKD.[4][2] Males and females should be equally at risk with Isolated PLD due to its autosomal inheritance pattern. Findings, however, indicate that there are six women for every man; this is because women have greater amounts of estrogen than men. The hormone estrogen has been

Pathophysiology

Isolated PLD results from embryonic ductal plate malformation of the intrahepatic bile ducts and cilia of the cholangiocytes. In normal bile duct formation, there is a complex sequence of events that involves both growth and apoptosis. In patients with isolated PLD, there is a disruption in this sequence, and no apoptosis occurs. As a result, complexes of disconnected intralobular bile ductules known as “Von Meyenburg complexes” form. Cysts arise from these complexes and continue to grow with time.[1][4] Cilia play an essential role in the production of cholangiocytes in the liver. Cilia can modulate intracellular levels of adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) and calcium, detect osmolarity changes in the bile, and have mechanosensory capabilities. Defects in the cilia lead to increased levels of calcium, which increases cAMP. The increase in cAMP drives the hyperproduction of polycystic liver disease, the treatment of cholangiocytes, and the formation of cysts. The increase in cAMP also alters the fluid balance in the lumen of the biliary ducts.[1]

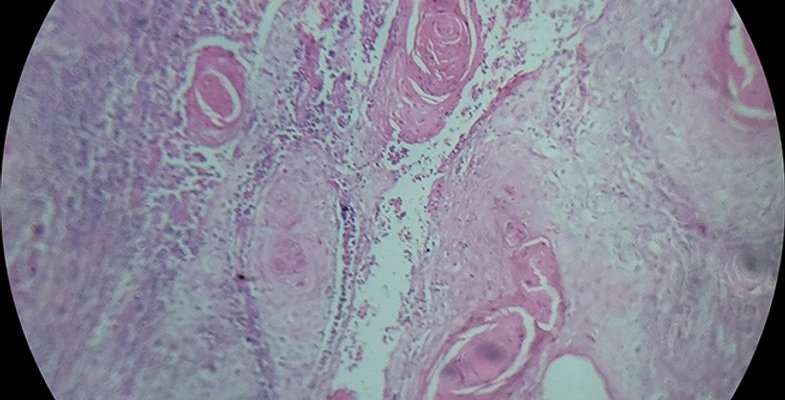

Histopathology

a cuboidalLiver cysts originate from medium-sized bile ducts. On histopathology, liver biopsy showed multiple diffuse cystic lesions resembling solitary cysts, lined by a cuboidal to flat biliary epithelium surrounded by fibrous stroma containing straw-colored fluid.[7][8] About 40% of patients with polycystic liver disease will have identifiable von Meyenburg complexes, and they do not contain pigmented material.

History and Physical

Most patients with isolated PLD are asymptomatic, and estimates are that 80% of patients are usually diagnosed incidentally on imaging studies. Symptomatic severity is dependent on the number, size, and location of the cysts. In symptomatic patients, the cysts are impeding nearby intrahepatic structures such as the inferior vena cava, hepatic veins, portal veins, or bile ducts. The common symptoms in patients with PLD include abdominal distension, shortness of breath, postprandial fullness, esophageal reflux, abdominal pain, and polycystic liver disease treatment-back pain. If patients have-reflux, early satiety, or postprandial fullness, they can be at risk for malnutrition and failure to thrive.

Compression of nearby vascular structures can lead to portal hypertension, and patients may present with variceal bleeding, jaundice, ascites, and/or encephalopathy.[2][3][9] Portal hypertension can be caused by a reduction in hepatic vein outflow or by compression of portal vein inflow. Signs and symptoms consistent with portal vein inflow obstruction are abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, and transudative ascites; this can result from direct compression from the cysts or the development of hepatic vein thrombosis from stasis.

Liver cysts can also cause a Budd-Chiari-like syndrome if venous drainage from the liver is obstructed and may present with the classic triad of abdominal pain, ascites, and hepatomegaly.[4][2][3] Patients who do develop advanced liver disease from isolated PLD are at risk for complications such as infections, torsion, rupture, and hemorrhage of the cysts.[1][10] End-stage liver disease, or cirrhosis, can develop with extremely increased liver volumes. Patients with severe PLD usually do not meet the Polycystic liver disease treatment Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) criteria. However, they can obtain transplants with exceptions for failure to thrive and malnutrition.

Evaluation

Imaging investigations are used to diagnose PLD. Regretfully, there aren’t any standardized radiologic diagnostic standards at this moment. The majority of people receive their diagnosis in their fourth or fifth decade of life. The subcapsular region of the polycystic liver disease treatment liver will have hyperechoic regions on ultrasound imaging. Another option is to use MRI and CT imaging, where the cyst will show up as well-defined and hypodense on non-contrast pictures.[1]

The standard diagnostic method for PLD is to apply the Reynolds criteria. This considers age, liver phenotype, and family history. It is advised to start with an ultrasound to look for kidney and liver cysts. The diagnosis of an isolated PLD should not be made until ADPKD has been ruled out. This may be done using the unified Ravine criteria. Unfortunately, renal cysts can coexist with isolated PLD in up to one-third of patients, Polycystic liver disease treatment making it challenging to differentiate between the two. When renal cysts and kidney phenotypes are present, patients with three or more renal cysts between the ages of 15 and 39 are diagnosed with ADPKD; those with two or more renal cysts between the ages of 40 and 59 are diagnosed with the disease.

According to certain research, patients with 15–20 cysts and no family history may be diagnosed with solitary PLD in occasional occurrences. Nonetheless, individuals must have a positive family history and be ruled out for ADPKD in accordance with Reynold’s criteria. If both of these conditions are satisfied, they are separated based on liver phenotype and age. The criteria for isolated PLD are met by individuals under 40 years of age who have one or more hepatic cysts, or by patients over 40 who have four or more hepatic cysts.[4][2]

There isn’t yet a diagnostic test in the lab for pure isolated PLD. The majority of individuals have normal synthetic liver function, while occasionally there may be slight increases in alkaline polycystic liver disease treatment phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT). Conversely, individuals with ADPKD exhibit changes in their glomerular filtration rate (GFR), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and/or creatinine levels, as well as indications of renal failure.[4]

Treatment and Management

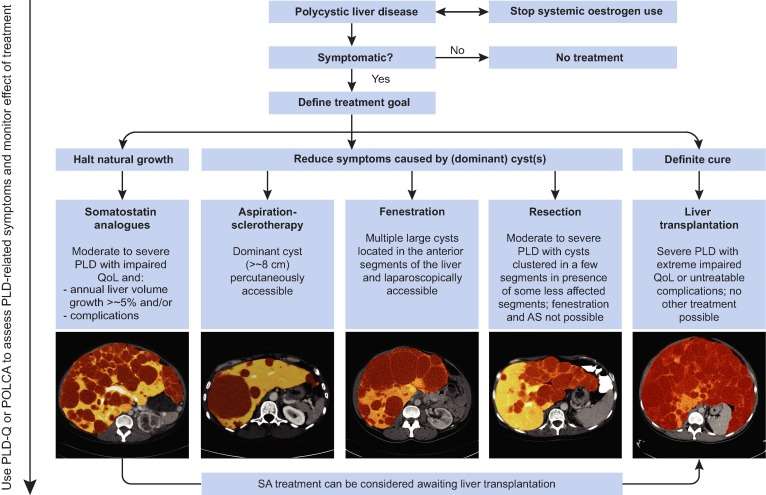

Most patients are asymptomatic, and no treatment or management is necessary for patients with isolated PLD. For symptomatic patients, the principal aim of treatment is to reduce symptoms Polycystic liver disease treatment involves decreasing cyst volume and liver size. These interventions can be divided into three broad categories: medical therapy, surgical therapy, and liver transplantation as a last resort.

Medical Therapy

There is a lack of adequate medical treatment options available for patients with PLD that are currently under investigation in clinical trials.[3]

Somatostatin Receptor Antagonist

Octreotide is a somatostatin receptor antagonist that has been shown to affect patients with PLD positively. Polycystic liver disease treatment cAMP plays a vital role in the development of cell proliferation and fluid secretion. Octreotide inhibits cAMP in cystic cholangiocytes and therefore leads to decreased fluid production and cell proliferation. Clinical trials have demonstrated its success in reducing liver volume and improving patient symptoms.[2][11] Current recommendations are to give a long-acting somatostatin analog once every month. However, there is currently not enough data on the long-term effects of remaining on these medications. Also, the cost of this therapy prohibits many patients from pursuing it as a treatment. It requires evidence of poor quality of life from moderate to severe disease to have the drug approved for treatment. Nevertheless, these medications are well tolerated, and the side effects, which include diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, and gallstones, are usually transient.[4]

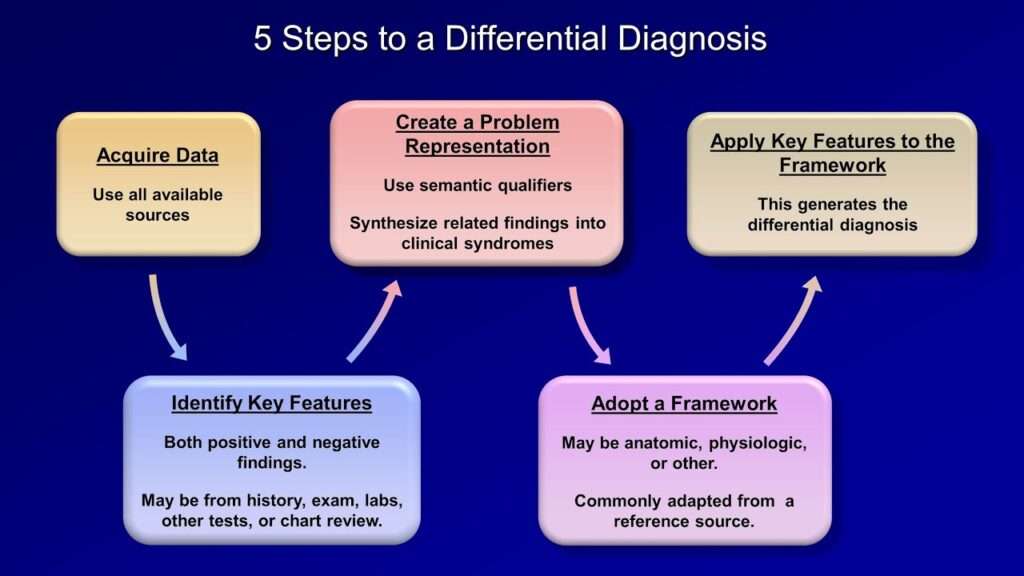

Differential Diagnosis

When considering PLD, other potential causes should be ruled out. These include neoplasms, infections, and trauma. Imaging allows the identification of PLD from hepatic metastases or an abscess. Other communicative biliary tree disorders to consider would be Caroli disease and Caroli syndrome. These two diseases are congenital genetic disorders of the intrahepatic bile ducts. These are typically seen in childhood, while isolated PLD occurs in adulthood. They are also associated with congenital hepatic fibrosis.[3]

Prognosis

PLD is a progressive disease, and only a small subset of patients develop severe symptoms. Supportive management with as-needed analgesics is the first-line treatment for PLD patients with polycystic liver disease. The primary aim of PLD treatment is to reduce liver volume to improve symptoms and quality of life.[9][1] The different invasive procedures that have shown improved outcomes include aspiration sclerotherapy, laparoscopic cyst fenestration, liver resection, or liver transplantation.[9] Although these procedures carry the risk of significant morbidity, their potential benefits should be carefully weighed against the complications of the procedures.

Complications

Several complications are notable in PLD patients. These complications can be broken down into intra-cystic complications and liver volume complications.

Intra-cystic Complications

Hepatic cyst hemorrhage

It typically manifests as acute right upper quadrant abdominal pain that progresses in the first few days and resolves spontaneously.[1] The etiology is thought to be high intracystic pressure, rapid growth, and direct trauma. Diagnosis is typically seen on ultrasound Polycystic liver disease treatment imaging, while CT or MRI imaging with contrast may be required to distinguish hemorrhage from malignancy.[20] Cystadenocarcinoma, cystic adenoma, and hemorrhagic polycystic liver disease treatment cysts all appear similar on ultrasound imaging.[2]

Hepatic Cyst Infections

Hepatic cyst infections are rare (1%) complications in patients with PLD and are believed to result from the translocation of bacteria from the intestines. It is typically present as right upper quadrant pain, fever, and malaise.[1] The imaging studies showing the hepatic cyst wall thickening and complex fluid are suggestive of infection but not accurate. The cyst aspiration showing the presence of inflammatory cells and bacteria is the gold standard for diagnosis. The two most common bacteria that cause these infections are Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) can be used to identify the infected cysts, as the epithelia of these cysts will accumulate the FDG. Unfortunately, it is not the gold standard, as the accuracy only seems to improve in the later stages of the infection.[21][22] Extremely high carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 levels were found in patients with hepatic cyst infection and declined during recovery.[23] Treatment is usually broad-spectrum antibiotics, and therapy is polycystic liver disease treatment narrowed down based on culture results. There is a 64% failure rate with just antibiotic treatment, and in these cases, cyst drainage is recommended alongside the antibiotics. C-reactive protein has also been found to be useful in monitoring treatment responses. [2]

Deterrence and Patient Education

PLD is a progressive disease, and only a small subset of patients develop severe symptoms. Supportive management is recommended for patients with mild symptoms, while patients with severe symptoms can be managed surgically, with liver transplantation being the only curative option for polycystic liver disease treatment. There is a lack of effective medical treatment options available for patients with PLD that are currently under investigation in clinical trials.[1][3] The risk factors for the development of severe PLD are age, female sex, prior use of exogenous estrogens, and multiple pregnancies.[26] PLD has an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, and the recurrence risk is 50%. Thus, genetic counseling is advised in patients severely affected by PLD because it may allow differentiation between ADPKD and isolated PLD.[27][28] Screening for PLD in the general population is not recommended since the prevalence of the disease is relatively low and it will be of low yield.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Enhancing outcomes in symptomatic patients with PLD requires an interprofessional team approach from primary care providers, hospitalists, hepatologists, specialty-trained nurses, pharmacists, and interventional radiologists and surgeons at times, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. Clinicians and other specialists will manage the condition overall, but medications should be polycystic liver disease treatment vetted through a board-certified pharmacotherapy pharmacist, who can collaborate on agent selection, verify dosing, and oversee the medication regimen for drug interactions. Specialized nursing can administer medications, monitor treatment effectiveness, and alert clinicians to any possible adverse effects. In surgical cases, nursing will have involvement throughout the process, from surgical prep to assisting during the procedure, polycystic liver disease treatment, and post-operative care, informing the clinician of any issues that they encounter. Such an interprofessional team of health professionals providing an integrated approach to the care of these patients can help to achieve the best possible outcomes. [Level 5]

1 thought on “Polycystic liver disease treatment”